AI did not just add a new tool to our teaching lives. It changed the conditions under which students read, write, plan, revise, and make meaning. When the environment changes that much, the job of teaching changes with it. The question is not whether we will “use AI.” The question is how we will help students learn in a world where the boundary between their thinking and a machine’s output can blur quickly, quietly, and sometimes convincingly.

That is why I keep coming back to literacies, not skills. Skills are interface moves. They matter, but they expire on a schedule that no one controls. Literacies are habits of attention that help us interpret what is happening, decide what matters, and act with intention. In other words, literacies make it possible to stay steady while the ground shifts.

AI is not one thing

When we say “AI,” we often talk as if it is a single object with a single set of effects. In practice, AI is an ecosystem: models trained on data, wrapped in interfaces, sold through incentives, and maintained through human labor that usually stays offstage. Students experience AI through a particular interface at a particular moment, with certain defaults and certain pressures. Faculty experience it through different interfaces, different stakes, and different expectations. Treating AI as an ecosystem helps us stop arguing about whether it is “good” or “bad” in the abstract and start asking better questions about context, use, and impact.

Courses and classrooms are also ecosystems. Policies, assignments, assessment practices, and norms all shape what students do. AI becomes part of that system whether we invite it in or not. If we want students to learn, we need to design for the environment they are actually navigating.

Five critical AI literacies

A workable approach begins with a set of literacies that faculty and students can develop over time. I use five. They are not a ladder where one comes first and the others follow. They are more like angles of vision. You can strengthen any one of them and see an immediate difference in student learning and faculty decision-making.

Conceptual literacy is about understanding what AI is and what it is not. Students benefit when they can describe, in plain language, how a system generates text or images and why it can sound confident while being wrong. Faculty benefit when we can explain the difference between an answer and an explanation, and between fluency and understanding. Conceptual literacy does not require technical depth. It requires enough clarity to avoid magical thinking.

Functional literacy is the practical side: how to use tools responsibly and effectively for legitimate purposes. This is where prompting, iteration, and workflow live. It also includes knowing the limits of a tool, recognizing when it is producing generic or distorted output, and understanding what information should never be entered into a system. Functional literacy is real, but it should not be the whole story. If we stop here, we produce students who can operate systems without good judgment about when and why.

Critical literacy asks students to interrogate outputs, assumptions, and power. Who gets represented, and who disappears. What gets treated as “normal.” Which sources get privileged, and which kinds of knowledge get flattened. Critical literacy also includes noticing when AI output turns complex ideas into smooth, confident summaries that feel like knowledge but do not behave like knowledge. It helps students slow down long enough to ask, “What is this doing to my thinking?”

Ethical literacy deals with responsibility, impact, and care. It includes academic integrity, but it extends beyond it. Ethical literacy asks students to consider consequences for real people: privacy, consent, attribution, and the hidden labor behind the systems. It also asks faculty to design policies that reduce harm without treating students as suspects.

Reflective literacy is the human core. It focuses on metacognition and agency: what I am trying to do, what I am outsourcing, and what I am learning in the process. Reflective literacy helps students notice when AI supports learning and when it replaces it. It also helps faculty notice when we are designing assignments that invite meaningful thinking versus assignments that invite the fastest workaround.

Together, these literacies give us a shared language. They let departments talk about student learning outcomes in a way that does not depend on any specific tool. They also give faculty a way to support students without having to become full-time AI explainers.

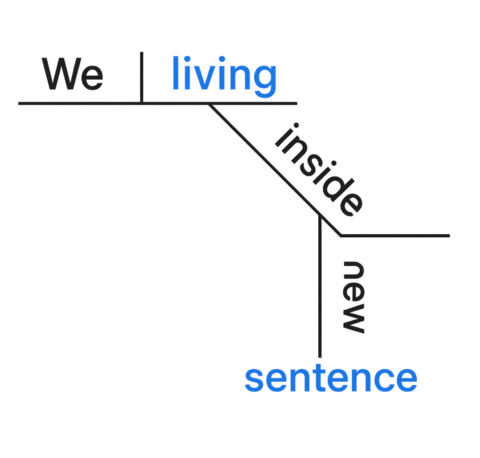

Naming versus knowing

One of the most persistent risks in AI-mediated learning is the illusion of understanding. AI can generate language that sounds like knowing. Students can quickly acquire what feels like mastery because the words arrive with polish and coherence. But naming is not the same as knowing. Knowing involves relationship: to a problem, to evidence, to context, to consequences, and often to other people. Knowing takes time. It also takes friction, which forces choices, revisions, and accountability to meaning.

If we want students to know, not just name, then assignments need to protect thinking. They need to make process visible and judgment unavoidable.

Neurodiversity belongs in this conversation

AI discussions often assume a single kind of learner. That assumption breaks down quickly. For some neurodivergent students, AI can scaffold: it can reduce the barrier of starting, support organization, or help translate an idea into a first draft that the student can revise. For other students, AI increases cognitive load. It can flood them with options, flatten their voice, or make it harder to trust their own judgment. The same student may experience both effects in different contexts.

A critical AI literacies approach helps because it does not assume one correct relationship to AI. It helps students build agency. It also helps faculty design supports that do not shame students who use tools while still protecting the integrity of learning.

Three design moves for faculty

If AI changes the environment, then faculty need practical design moves that hold up over time.

- First, make process visible. Design assignments where students show how they arrived at an answer: drafts, checkpoints, revision notes, design rationales, or brief reflections that connect choices to learning goals. This is not busywork. It is a way to bring thinking back into view.

- Second, build comparative iteration. Ask students to generate alternatives, test approaches, and compare results. In an AI world, the first answer is cheap. Judgment is not. Assignments that require comparison and justification help students practice the kind of thinking that AI cannot do for them.

- Third, protect voice and judgment. Students need room to sound like themselves and to make claims they can stand behind. We can design prompts that invite specificity, local context, and disciplinary stance. We can ask for decisions with consequences: what to include, what to exclude, what evidence matters, what tradeoffs they accept, and why.

These moves support integrity, but they also support learning. They help students develop an internal sense of authorship and accountability, which matters long after a particular tool falls out of fashion.